[ad_1]

Men with iron overload due to hereditary hemochromatosis are at increased risk of developing dementia, an analysis of UK Biobank data indicates.

Results of a large analysis showed that among men who had two mutations that cause hemochromatosis (HFE C282Y homozygotes), brain iron deposition was more marked in dementia-relevant areas, and they were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with dementia over a 10-year period than men who did not have these mutations.

Dr Janice Atkins

“Hereditary hemochromatosis is the most common genetic disease in populations of Northern European ancestry,” Janice Atkins, PhD, Institute of Biomedical and Clinical Sciences, University of Exeter Medical School, Exeter, United Kingdom, told Medscape Medical News.

“It is vital that patients with hereditary hemochromatosis are diagnosed and treated earlier. This is likely to prevent substantial excess morbidity, including from dementia but also from liver disease, liver cancer, diabetes, and osteoarthritis,” said Atkins.

“Hereditary hemochromatosis can be easily tested for, and treatment with venesection to lower iron levels is safe and effective,” she added.

The study was published online February 2 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Table of Contents

Modifiable Risk Factor?

Using the UK Biobank, the researchers estimated hemochromatosis genotype associations with brain MRI measures and with incident dementia diagnoses. They focused on men who were homozygous for HFE C282Y, who develop the majority of hemochromatosis-related physical diseases.

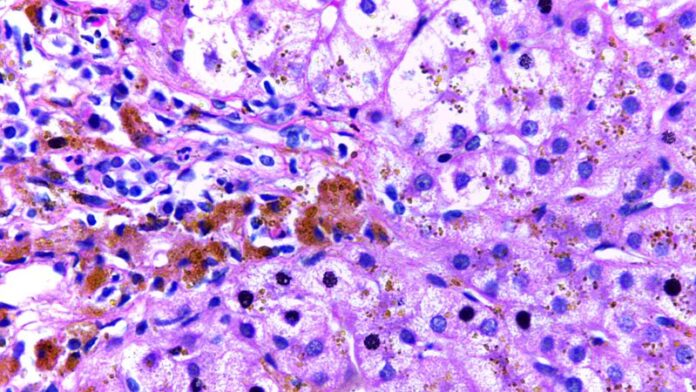

They found that measures of MRI T2* signal loss ― an indicator of more iron deposition ― were substantially lower in the 78 HFE C282Y homozygous men compared with 11,082 men who did not have HFE mutations.

This was true across a number of brain regions, including the putamen, the caudate, and the nucleus accumbens, “but notably also within important cognitive regions” of the thalamus and the hippocampus.

During follow-up, 25 of 78 men who were homozygous for HFE C282Y and 1358 men who did not have HFE variants developed dementia. The risk significantly increased among men homozygous for HFE C282Y (hazard ratio [HR], 1.83; 95% CI, 1.23 – 2.72; P = .003).

Men who were homozygous for HFE C282Y were also more likely to develop delirium during follow-up. Delirium has also been linked to dementia (HR, 1.82; 95% CI 1.21 – 2.72; P = .004). There was no association with mild cognitive impairment, stroke, and transient ischemic attack.

There were no associations in women who were homozygous for HFE C282Y or in persons who were heterozygous. “The risk seems to be lower in women, who are partially protected by menstrual blood losses,” Atkins told Medscape Medical News.

In a statement, coauthor David Steffens, MD, with the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut, said, “This study adds to the list of modifiable factors that may point to prevention of dementia.

“If our results are replicated, it may become routine for clinicians to test for hemochromatosis in the evaluation of patients with memory complaints and in the screening of older asymptomatic patients,” Steffens added.

Replication Needed

Reached for comment, Frank J. Wolters, PhD, Department of Epidemiology and Neurology, Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, said that it was an interesting study “more firmly establishing brain iron accumulation among the list of organs that can be affected by hemochromatosis.

“Hematochromatosis can also lead to iron accumulation in, for example, the liver, pancreas, and the heart. Recent cohort studies have linked disturbed liver function, endocrine dysfunction, and heart failure to dementia, so it would be interesting to see to which extent these associations might be influenced by iron accumulation,” said Wolters.

“As mentioned by the authors, evidence about the impact of hematochromatosis on the risk of Alzheimer’s disease isn’t entirely consistent, and the number of homozygous carriers is generally small, so replication of these findings is needed,” Wolters cautioned.

“Nevertheless, this study provides an important step forward in our understanding of the effects of iron on the brain and illustrates for future studies the importance of singling out the homozygous from the heterozygous carriers,” he added.

In a recent analysis of data from the Rotterdam Study, Wolters and his colleagues showed that abnormal hemoglobin levels — both low and high — are associated with an increased risk of developing subsequent dementia, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

This work was funded by UK Medical Research Council. Atkins and Wolters have no relevant disclosures.

J Alz Dis. Published online February 2, 2021. Full text

For more Medscape Psychiatry news, join us on Facebook and Twitter.

[ad_2]

Source link