[ad_1]

Screening for cardiac amyloidosis and excluding patients with cardiac amyloidosis from trials of new therapies for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) may increase the chances of finding drugs that actually work, a new analysis suggests.

When investigators retrospectively studied a cohort of 317 patients with HFpEF related to cardiac amyloidosis, they found that between 16% and 65% of them would have been eligible for one or more of a series of eight recent failed HFpEF trials, including the PARAGON-HF trial (sacubitril/valsartan), TOPCAT (spironolactone), and CHARM (candesartan).

For PARAGON-HF alone, they found that almost half of the cohort of patients with cardiac amyloidosis would have met inclusion criteria for that trial.

“Our results demonstrate that the patient selection criteria used in clinical trials in patients with HFpEF fail to exclude patients with cardiac amyloidosis,” Silvia Oghina, MD, from the French Referral Center for Cardiac Amyloidosis at Henri Mondor Teaching Hospital, Creteil, France, and colleagues conclude. The group’s study was published online February 3 in JACC: Heart Failure.

There are three main types of cardiac amyloidosis: light-chain amyloidosis, hereditary transthyretin amyloidosis (ATTR), and wild-type ATTR. The cohort studied by Oghina and colleagues included all three types.

“The absence of efficacy of the interventions tested in these trials may be ascribable, at least in part, to the greater refractoriness to treatment and higher mortality that characterize cardiac amyloidosis compared with other causes of HFpEF,” they say.

The history of HFpEF is awash with failed trials in which investigators sought efficacious therapies. Clinical trials involving aldosterone antagonists, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitors, beta blockers, and nitrates all failed to meet primary efficacy endpoints.

That said, in December 2020, on the basis of a new analysis of the PARAGON-HF data, a US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) expert panel backed a bid to expand the indication for the approval for sacubitril/valsartan to include individuals with HFpEF.

Scott D. Solomon, MD, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts, principal investigator of the PARAGON-HF trial, isn’t convinced the findings would have been different had they formally screened for cardiac amyloidosis, which would have required using techniques that were not yet established at the time the trial was designed. Noting that patients with overt amyloid were excluded from the trial, he had this to say about this new analysis:

“I agree with the authors that patients with unknown amyloid heart disease might contaminate the HFpEF population, including those enrolled in trials. However, the number is likely relatively small, and most likely represented in the higher LVEF patients, and might explain some of the heterogeneity we have seen in recent HFpEF trials,” he said.

Solomon added that, going forward, “it is prudent to consider amyloid screening in some patients with HFpEF, particularly those with higher LVEF and men.”

“This manuscript gets to an important issue that all of us in the cardiac amyloidosis community have suspected for a long time, which is that a substantial proportion of patients in HFpEF trials have unrecognized amyloidosis,” said Ronald Witteles, MD, co-director of the Stanford Amyloid Center at Stanford University, in California.

“It is not at all surprising that this subset of patients with amyloidosis would not have as good a response to the therapies as compared to a more, quote unquote, ‘standard’ HFpEF population,” he added in an interview with theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology.

The problem, he thinks, is that clinicians persist in considering HFpEF a diagnosis rather than a syndrome. “If someone has HFpEF, then you need to say they have HFpEF due to blank ― whether it’s hypertension, amyloidosis, or whatever ― and then you treat them accordingly,” said Witteles, who was not involved in this research.

“I mean, we’d never say someone has renal failure, period. We’d say they have renal failure due to, say, diabetes,” he said.

More significant than the impact of undiagnosed cardiac amyloidosis on HFpEF trial results is the fact that, as of mid-2019, there has been an FDA-approved therapy for the most common type of cardiac amyloidosis — ATTR. Patients with undiagnosed conditions, by definition, are also patients whose conditions go untreated.

First presented at the European Society of Cardiology 2018 meeting and covered by theheart.org | Medscape Cardiology at the time, the ATTR-ACT trial showed that, compared to placebo, treatment with tafamidis improved both survival and quality of life for patients with transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy.

Look and You Shall Find

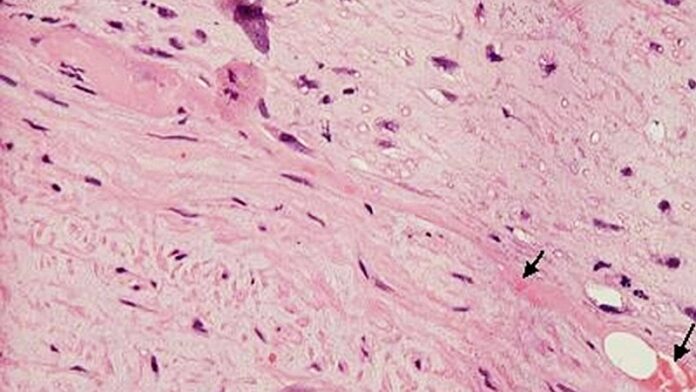

Until very recently, patients who were being considered for inclusion in HFpEF trials were not routinely screened for cardiac amyloidosis, for a simple reason: definitive diagnosis required endomyocardial biopsy as well as other tests, which set the threshold for screening high.

Currently, screening is relatively simple and requires only some blood tests and a readily available nuclear imaging scan. The details of such screening were elucidated in a recent article for which Witteles served as senior author.

In a State-of-the-Art Review published in 2019 in JACC: Heart Failure, Witteles and coauthors outlined a simple two-step approach to screening for cardiac amyloidosis. The first step involves lab work to rule out light-chain amyloidosis, after which a technetium-labeled cardiac scintigraphy scan can be used to rule out ATTR cardiac amyloidosis.

Witteles and colleagues also provide a simple algorithm to decide whom to screen: men older than 65 and women older than 70 with heart failure and left ventricular hypertrophy (≥14 mm). For patients for whom heart failure has not been diagnosed, they provide a list of “red flags” that should stimulate screening, including bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome, mildly increased troponin levels on multiple measures, and symptoms of polyneuropathy.

“Every time I attend on the cardiology service for 2 weeks, I diagnose at least one patient with cardiac amyloidosis,” said Witteles. “When you know how to look for it, you find it, because it’s really not rare, particularly if you’re looking in a population of older individuals with heart failure.”

Oghina has received honoraria from Pfizer, which is the manufacturer of tafamidis, which is the only FDA-approved therapy for transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Witteles has consulted for and has participated in clinical trials for Pfizer and other companies involved in developing treatments for cardiac amyloidosis.

JACC: Heart Fail. Published online February 3, 2021. Abstract

For more from the heart.org | Medscape Cardiology, follow us on Twitter and Facebook.

[ad_2]

Source link